The catastrophic flood in Valencia on 29 October has opened the debate in Spain on the functioning of warning and response systems for natural disasters. In recent days, many media outlets have published information about the protocols governing emergency alerts and, in particular, the system EN-Alertwhich it is useful to put into context.

A early warning system disaster preparedness is a critical tool for a modern society. The malfunctioning of these increased losses in catastrophes such as the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia (170,000 dead) or the management of the Fukushima disaster in Japan. In the massacre of 7 October 2023, Hamas terrorists launched one of the most heinous computer attacks in history.

history against Israeli emergency systems, with the aim of causing as much damage as possible to the civilian population.

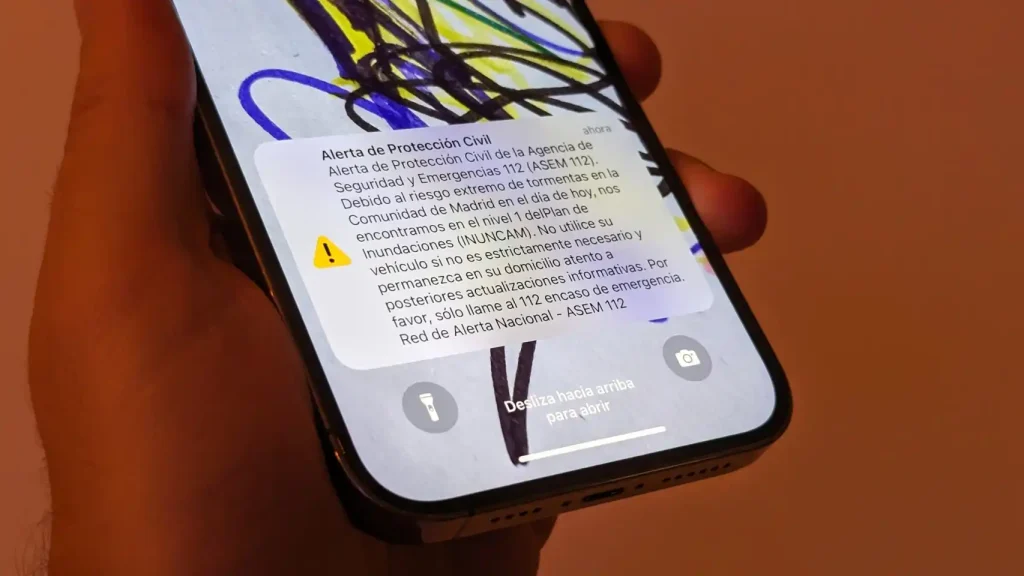

Aware of its importance, all countries are trying to improve their warning systems. Following European directives in 2018, Spain has implemented the system EN-Alerta relatively new system in Spain.

The first test runs took place in September 2022 and the technological infrastructure was fully implemented in February 2023. But that does not mean that the system is operational. Since then, according to the Ministry of the Interior, "it has been made available to state and regional civil protection authorities".

Since then, the Ministry of the Interior, as responsible for the development, has gradually implemented the system in different autonomous communities that are users of the application. The first real use occurred in September 2023, in the Community of Madrid, in the event of another catastrophic storm, just over a year ago.

It is difficult to know which regions have the system fully implemented. We know that Madrid, Andalusia and Catalonia have it in place because it has already been used. But, for example, in the Canary Islands it is announced that it is in the process of being tested as indicated in this news item. We will analyse the case of Valencia later on.

How does ES-Alert work?

ES-Alert provides a very powerful tool for Civil Protection authorities. In the past, warning systems relied on messages sent by the media (need to be connected), acoustic alarms (difficult to interpret) or public address (coverage in very small urban areas).

ES-Alert, on the other hand, allows a warning message to be sent to the population with very precise information, adapted to the type of catastrophic event, targeted at a very delimited area and in a very short period of time.

The system is based on Cellbroadcast technology and takes us back to the origins of the mobile phone network. A few weeks ago at IMMUNE we organised a master class for software development students with one of the people who collaborated with its implementation in Spain, Raquel Pérez Serranofrom Telefónica Tech, who explained how it works.

Recall that this is nothing more than a collection of radio-link base stations, each with a small geographic coverage. Each base station communicates with the radio terminals/mobile phones that are activated in its coverage area.

What we see on the mobile phone as voice, text, images or Internet services is transformed into a set of radio signals, through a series of software layers, which is transmitted via the nearest base station. To provide service, the phone is always in communication with the nearest "antenna" or "cell".

This is the power of ES-Alert. The system allows messages to be sent specifically to an antenna or a group of antennas in a given geographical area and distributed almost simultaneously to all mobile phones that are connected to that antenna at a given time. Even to those "foreign" mobiles that are connected to the antenna for roaming.

The alert message is no more than a set of electrical pulses on a radio frequency, which the phone will interpret as a control message or Level 1 instruction coming from the "antenna", something that all mobile phones must do by design. It therefore gives it the highest priority and does not pass through Internet or operating system filters. It is not possible for the user to disable them. Some other important features:

- It allows messages of up to 1395 characters to be transmitted.

- The transmission range can be varied, from a single cell to the entire network.

- It is not affected by traffic load; therefore, it is especially usable during a disaster when peak data loads (social networks and mobile applications), regular use of SMS and voice calls (mass calling events) tend to significantly slow down mobile networks.

For these reasons, the emergence of ES-Alert in the civil protection This means that all alert notification procedures need to be reviewed, as the scenarios are very different from those we had using other technologies.

Consequences of the implementation of ES-Alert

Activating a disaster notification mechanism is not an easy decision. Doing it too quickly or too lightly makes the system lose credibility with the public. A couple of false alarms do a lot of damage, not to mention the social consequences (lost school days, rescheduled medical appointments, lost work hours).

On the other hand, delaying too long in activating it, or failing to do so, can lead to avoidable human and material losses. When is the right time? The tragedy in Valencia will lead to a forensic analysis of alert management procedures before future disaster situations. A painful learning process that is likely to save many people in the future. Probably the only sense that the loss of so many human lives can make.

But what needs to be reviewed from the point of view of ES-Alert implementation?

First of all, the system, however powerful it is, does not activate itself, it requires a human decision. We are now in a position to notify the population of an incident in minutes or seconds. So we must speed up decision-making so that what we gain in notification time is effective and is not neutralised in long processes of analysis and discussion, as Alicia Marti explains.

in this article published in the newspaper La Razón (edition of 8/11/24).

In addition, clearly define the criteria for activation of the system in such a way that it is impersonal. That is, activation should not depend on the arbitrary judgement of one person (be it a technical or political position). For this, the discussion about notification criteria should be lengthy, but in a phase of normality, never at the time of the disaster.

For this, the decision-maker must have been trained in clear scenarios against which to compare the situation he or she faces, reducing uncertainty and understanding that following the protocol gives an explicit endorsement of his or her action. It frees you from the fears and tensions of failing to make a decision. And, of course, all this needs to be trained through drills.

This does not seem to have been the case in Valencia. In the aforementioned article in "La Razón", the Valencian government's own minister, Salomé Pradas, acknowledges that "she did not know this mechanism (EN-Alert) and explains that there is currently no protocol in place to implement it, as it is pending approval by the National Civil Protection Commission".

We could speculate on what would have happened if the catastrophe had occurred a few months later, with the new protocols in place and with training for those responsible (the councillor had not been in office for more than three months). But a process of implementing a new technology cannot be considered finished until the users have adapted their processes and have been trained to use it.

Secondly, we must ensure that before activating the system, the decision-maker has reliable real-time information on all the variables that have an impact on the decision. We would not be taking advantage of the speed of ES-Alert if we have to wait hours for emails with flow readings ("El polémico email de las 18.43 de la Confederación del Júcar no se envió antes porque los operarios estaban en la reunión de emergencia", Isabel Miranda para ABC, 5/11/24).

Or if we receive contradictory data from different teams deployed in the field ("La Generalitat sent the alert to mobile phones because it feared the Forata dam would burst, not because of the flooding of the Poyo ravine, of which it was not warned", El Español, 7/11/24). In short, the entire flow of information needs to be reviewed.

If we can ensure a verified and continuous flow of relevant data, we could even consider automatic update scenarios, reporting real-time changes in disaster forecasts and affected areas.

Today, technology allows us to do so.

Finally, we must not become complacent or fall for the magic solutions provided by technology. It must be understood that an excellent warning system is a necessary but not sufficient condition to prevent a disaster. Moreover, it is very likely, without taking responsibility away from the current authorities at all levels of administration, that the Valencia tragedy has been incubating over the last 30 or 40 years.

At cybersecuritywe make much use of the concept of "assumed breach"("assuming the gap"). It basically implies that even if we have an unlimited budget and take all possible preventive measures, something unforeseen can always happen and data processing can be interrupted. The only way to react to such a situation is to raise awareness, educate and train people in contingency planning.

In other words, a timely early warning is useless if the public does not know how to react to it. If they don't know to stay indoors, abandon cars wherever they can, seek high ground and stockpile supplies in case they are cut off. Have spare mobile phone chargers in case of power failure, tools, appropriate clothing and many other precautions. If

the local authority does not provide parking spaces at high places, evacuation sites or pre-determined supply points.

Preparing for such a disaster (which occurs every many years) takes a long time. It is known that health awareness campaigns (the most effective of all) barely manage to mobilise behavioural change in 5% of the population at each iteration.

Therefore, a sustained awareness-raising effort is needed, starting with school children, and continuing with specific plans by public and private organisations in the area. This is the only way to ensure that warnings are effective, however rapid they may be.

If we start now, we may be in a better position to cope better with the next big flood.